-

2017-04-17

Background

In India, General Anti-Avoidance Rule (“GAAR”) shall be effective from 1 April 2017 i.e. applicable from AY 2018-19 onwards. GAAR enables the tax authority to go into substance of the transaction and to disregard if the main purpose of such an arrangement is to obtain tax benefit and there is no commercial or business justification for creating such arrangement other than to obtain the tax benefit.

Though such principle to go behind the legal substance of transaction was already upheld by the Supreme Court of India (e.g. famous McDowell decision) in various judicial pronouncements, GAAR enacts such principle under the Act and provides basis on implementation of such principle.

However as provided under the Act, GAAR shall not apply in certain cases. Further any income arising on transfer of investment made up to 31st March 2017 is out of purview of GAAR. The tax authority in such exceptional cases does not have power to invoke GAAR.

The question still remains is whether a tax authority can question the vires of such transactions by invoking judicial decisions of Apex Court on the subject matter of tax avoidance to such carved-out cases? The discussion in this paper is on around to this question.

To get an understanding on this proposition, we need to first go through the journey of different rulings of the Apex Court over a period of time on the aspect of tax avoidance. Thereafter, we need to examine whether and how GAAR effectively covers all the aspects of tax avoidance as emanating from the pronouncements of the Apex Court.

Judicial view on tax avoidance

It is judicially accepted that tax planning, within the four corners of law, is permissible under the Income Tax Act,1961 (“the Act”),whereas the tax avoidance or tax evasion has no place in law. Without going into the issue of morality of tax avoidance and its acceptable level, while interpreting the provision of the Act, the pre-dominant judicial view is that the colorable device cannot be used as a part of tax planning.

The very concept of tax avoidance can be traced back to Duke of Westminster's ([1936] AC 1) case in year 1936. It was this landmark case that marks the beginning of the concept of substance v. form. In this case, certain payments were made by the taxpayer to domestic employees in the form of deeds of covenant (which were tax-deductible) instead of regular wages (which were not tax-deductible). The House of Lords refused to disregard the form of the transaction over the substance and in doing so laid down the cardinal principle that “every man is entitled, if he can, to order his affairs so that the tax attaching under the appropriate Acts is less than it otherwise would be”.

In IRC v. WT Ramsay Ltd (1981) ([1982] AC 300), the House of Lords cautioned against a series of transactions which are pre-ordained, inserted into which are steps that have no commercial purpose apart from tax avoidance. In this case the Court held that the principle of the Duke of Westminster's case must not be over extended. If it is visible that a document or a transaction was intended to be a part of a nexus, then even the form of the transaction cannot prevent it from being regarded as such. Effectively Ramsay’s approach is to give more weight to substance as compared to its form.

In India, the judicial interpretation of substance over form was given by Apex Court in Mc Dowell [TS-1-SC-1985-O] in year 1985. As famous as McDonalds, it was a landmark ruling in the context of tax planning, tax avoidance and tax evasion. In this case, the Apex Court after considering various foreign case laws as discussed above, held that Tax planning may be legitimate provided it is within the framework of law. Colourable devices cannot be part of tax planning and it is wrong to encourage or entertain the belief that it is honourable to avoid the payment of tax by resorting to dubious methods. It is the obligation of every citizen to pay the taxes honestly without resorting to subterfuges.

The Apex Court went on saying that courts are now concerning themselves not merely with the genuineness of a transaction, but with the intended effect of it for fiscal purposes. No one can get away with a tax avoidance projects with the mere statement that there is nothing illegal about it.

Many than more times the ratio of this decision has been used by the tax authorities to defend their position. In fact, the Apex Court also elaborately dealt this decision in the case of Azadi Bachao Andolan and lately in case of Vodafone.

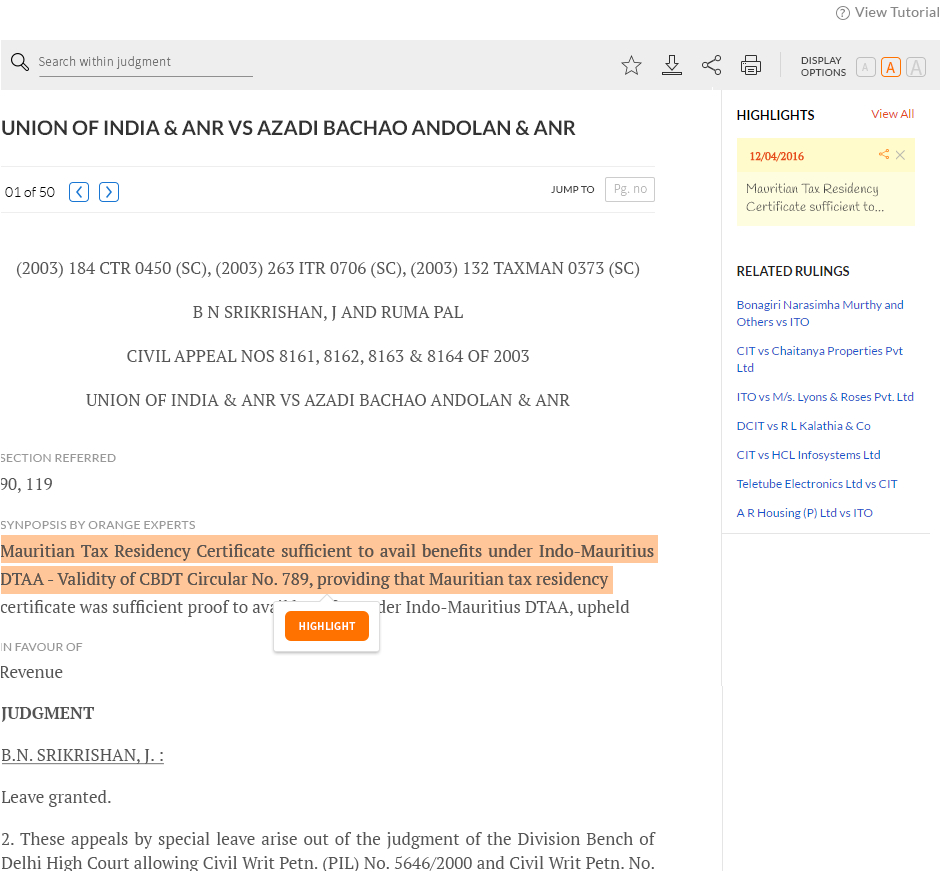

In the case of Azadi Bachao Andolan [TS-5-SC-2003-O] in year 2003, the Apex Court gave radical finding that there is no complete go bye to Westminster’s principle. The Apex Court, while upholding the treaty shopping based upon tax residency certificate of Mauritius Authority, held that one could not accept the submission that an act which is otherwise valid in law can be treated as non est merely on the basis of some underlying motive supposedly resulting in some economic detriment or prejudice to the national interests, as perceived by the respondents.

In this case while analyzing its own decision of Mc Dowell, the Apex Court held that Westminster’s principle continues to be alive. The Court noted that even in Mc Dowell, except Mr. Chinnappa Reddy, J., it does not appear that the rest of the Judges of the Constitutional Bench contributed to this approach. The Apex Court held that an attempt by resident of a third party to take advantage of existing provisions of double taxation avoidance agreement is not per se illegal unless such entity is per se sham or colorable device. Tax Department cannot alter such arrangement merely because it is detrimental to revenue.

Lately in Vodafone [TS-23-SC-2012-O] case in 2012, the Supreme Court held that the Income-Tax Department could always apply the ‘substance over form’ principle or ‘pierce the corporate veil’ if they establish that a transaction is a sham or tax avoidant. While, upholding non- taxation of indirect transfer in India in absence of any specific provision, the Apex Court held that one has to ‘look at’ the entire transaction as a whole and not “look through” by adopting a dissecting approach. The Apex Court clearly held that there is no departure of Apex Court in the case of Azadi Bachao Andolan from the ratio of the judgment delivered in the case of Mc Dowell.

All the above decisions reflect that the tax avoidance is not permissible though it took different approach on characterizing an arrangement as tax avoidance starting from Mc Dowell to Vodafone. However, with due respect to such decisions, the question of deciding what constitute tax avoidance was unclear or undefined. On the contrary the approach to find existence of tax avoidance, at least in my view, was at variance.

At the same time, it cannot be said that but for GAAR provisions introduced recently, McDowell’s decision has no ground to play. It can be safely said that none of the subsequent decisions have dissented from the view of McDowell, though may have worked in diluting the impact thereof in certain specific circumstances. The spirit of McDowell is still haunting. No pun intended.

Codification of GAAR & coverage of judiciary view

GAAR standardized the approach to deal with situation of tax avoidance by codifying what constitutes tax avoidance. The Memorandum to the Finance Bill, 2012 while explaining the need for introduction of GAAR provision mentioned that though there are some specific anti-avoidance provisions under the Act, general anti-avoidance has been dealt only through judicial decisions in specific cases. It is to codify the doctrine of "substance over form", where the real intention of the parties and effect of transactions and purpose of an arrangement is required to be seen, GAAR provisions are introduced under the Act.

The starting point under GAAR is to characterize an arrangement as Impermissible Avoidance Arrangement (IAA).As per the definition as provided under section 96(1) of the Act, an arrangement would be treated as IAA if it fulfils following conditions;

1. Main purpose of such arraignment is to obtain a tax benefit and

2. such arrangements fall within any of the following situations;

a. arrangement has created rights and obligations which are not ordinarily created between the parties dealing at arm’s length,

b. the arrangement results in misuse or abuse of provisions of the Act,

c. the arrangement lacks commercial substance or is deemed to have lacked commercial substance as defined in section 97 in whole or in part;

d. is entered into in a manner which are not ordinarily employed for bona fide purposes.

The entire emphasis of treating an arrangement as IAA is on substance of the transaction rather than its form. The objective is to test the purpose of an arrangement as reflected by its form. In nutshell, in any tax planning, in addition to saving in tax cost, a taxpayer is required to justify what other commercial objective he has achieved to treat his tax planning as permissible under the Act.

If one looks into the characteristic of such IAA, it reflects what Mc Dowell’s has covered on the aspect of tax avoidance. The Apex Court held that every taxpayer is entitled to arrange his affairs within the four corners of law and if the transaction has commercial and economic substance, the same cannot be disregarded by the Revenue merely because it results in reduction of tax liability. The Revenue can disregard only those arrangements which are artificial and colourable. GAAR therefore defines tax avoidance in consonance of such principle.

GAAR enacted the understanding of Apex Court on the concept of tax avoidance to test real intention of the parties. If there is any abuse or misuse of provision of the Act, GAAR can be invoked. If any arrangement is artificial or colourable having no business substance, GAAR can be invoked. This is what Apex Court upheld in its earlier decisions starting from Mc Dowell to Vodafone.

In fact, on detailed scrutiny, scope of GAAR is much wider than what was explained by the Apex Court in Mc Dowell. The deeming definition of lack of Commercial substance as provided under section 97(1) of the Act includes round trip financing, accommodating party, element of offsetting or cancelling effect of individual transactions, impact of arrangement on business risks and cash flows, location of assets or transaction or a place of residence of any party as one of the elements to treat any tax planning as tax avoidance. Barring the raging debate of treaty override with respect to GAAR, the GAAR provisions can have the impact of nullifying the decision of Apex Court in case of Vodafone, in so far as it pertained to the ratio where it was held that treaty shopping is permissible. If lower tax jurisdiction has been exploited solely for the purpose of obtaining tax treaty benefit, GAAR can be invoked. This clearly establishes that GAAR is not merely a codification of what was already provided for in McDowell’s decision but goes much beyond it and is therefore wider in its application as compared to existing judicial pronouncements.

Invocation of judicial view on exempted cases of GAAR

In my view GAAR is an extended and codified version of judicial anti-avoidance rule (“JAAR”) as spelt out by Apex Court in various decisions starting with Mc Dowell to Vodafone. This puts up an interesting question about whether the judicial view still prevails, at least to the extent of cases where GAAR has excluded its application.

Under Rule 10U, specific exemption is provided to certain cases where GAAR shall not apply. These are:

a. any income accruing or arising to any person from transfer of investment made up to 31 March 2017.

b. An arrangement where the tax benefit in the relevant assessment year or years arising to all the parties taken together does not exceeds by Rs.3 Cr.

c. FII, (i) which has not taken any tax treaty benefit; and (ii) has invested in listed securities, or unlisted securities with the permission of the competent authority in accordance with SEBI regulations/such other regulations as may be applicable.

d. Non-Resident person in relation to investment in offshore derivative instruments or otherwise in any FII.

As discussed above GAAR encompasses all the aspects of the JAAR and codifies the law which is not leaving any aspect of the JAAR conceptually. While GAAR provides for a detailed procedural provisions for ensuring its applicability only after a detailed scrutiny, it also excludes certain cases by creating specific carve outs. The Parliament while enacting GAAR has given due consideration to the recommendation given by the Shome Committee (“the Committee”), formed by the Central Government on GAAR, especially for keeping the procedural safe guards and creating the carve outs.

On the issue of grandfathering of existing investment, it was noted by the Committee that FDI and FII growth story cannot be overlooked. Stakeholders pointed out that substantive investments have come to India by way of portfolio investment or foreign direct investment from two jurisdictions Singapore and Mauritius based on the effective assurance that, on exit no tax would be levied in accordance with the relevant tax treaty and the said view is further upheld in case of Azadi Bachao Andolan. Now, it would be unfair to challenge those investments under the garb of GAAR. In the light of the above the Committee has suggested not to apply the provision of GAAR on the existing investment on its exit. Accordingly, the exception has been provided under Rule 10U.

The Committee further recommended not to make the GAAR applicable where tax benefit does not exceed Rs.3 Cr. so as to restrict its applicability to high value of sophisticated structures. The limit of Rs.3 Cr. was justified in the report based on data available with the committee wherein PBT above 10Cr. were observed in only 6141 companies (out of total 4,59,270 companies) which accounted for 87% of total corporate tax revenue. Thus, with an intention to exclude balance 4,53,129 companies from the rigors of GAAR, the limit of Rs. 3.00 Crore of tax saving was suggested. This reflects materiality approach on the part of the Committee to invoke GAAR.

The exemption to FII (not claiming any tax treaty benefit) and to a non-resident in FII (whether such FII is claiming or not claiming any tax treaty benefit) from applicability of GAAR under Rule 10U was also one of the recommendation of the Committee.

The exclusion therefore represents a conscious decision on the part of the legislator for not invoking GAAR in such cases.

It is in light of the above, it can be safely concluded that the GAAR is a conscious attempt to codify and give legislative recognition to the JAAR provisions. When such a conscious call is taken, it is also decided to exclude certain entities, transactions or arrangements out of the purview of the GAAR. It would therefore be clearly concluded that legislature had no intention to include such entities, transactions or arrangement under JAAR.

Further it is an acceptable cardinal principle of interpretation that the latter law should prevail over earlier law. Before GAAR, the decision of McDowell shall be regarded as law of land dealing with the subject of tax avoidance. Accordingly, the Judge made law could prevail. However, on introduction of GAAR, which has codified the JAAR on tax avoidance, the Judge made law is enacted under the Act & become part of the Act to deal with the situation of tax avoidance. Since the legislature consciously decided not to apply such provision in certain cases, it can be safely concluded that the legislation also consciously considered to exclude these cases also from JAAR. Therefore, McDowell’s case now cannot be invoked in such carved-out cases.

Closing remarks

Any contrary view on the above issue would make the objective for such exemption from GAAR redundant. In fact, in case of excluded cases, even the procedural protection would not be available and therefore the GAAR provisions can be applied more rigorously. This is neither the intention of introduction of GAAR nor is the intention of creating the carve out.

The exclusion has been provided to give tax certainty to certain class of investor and income arising on transfer of investment made prior to 1 April 2017 as suggested by the Committee formed by the Central Government. Further as wide power is made available through GAAR, on the materiality principle, its applicability has been restricted to cases where tax benefit does not exceed Rs.3 Cr. to avoid unintended harassment & cost of litigation.

Accordingly post introduction of GAAR, JAAR cannot be used in cases where provision GAAR cannot be invoked in view of specific exemption contained under the law.

However, it would be difficult to argue that JAAR is not applicable to cases of assessment year commencing on or before 1.4.2017, though such case may fall under any exemption category or grandfathering provision contained in Rule 10U.